How Old Are You? Why 65 Really Is the New 60

July 23, 2025

In pulling together the information for this series of blogs, I was struck by the lack of consistent sub-categories of demographic groups of Seniors based on age. Based on my personal observations I believe in the three phases of retirement: Go-Go, Slow-Go, and No-Go years. But I had no way to objectively define them.

The Search for Senior Age Categories

I have seen definitions used by various Government Departments for what constitute various age brackets for older Americans – but none seems to be consistently used, other than the vague descriptor of “Senior”, shortened from the original “Senior Citizen” for reasons that I still do not understand. Government retirement benefits begin at 20 years of service for the military (as early as age 38) and extend to 67 years-old (for full Social Security), for long suffering Baby Boomers born after 1955. Clearly “Senior” can mean different things when monetary benefits are involved!

Social Security started in 1935, with old age benefits beginning at age 65, when the life expectancy for an American was 60 for men and 64 for women. Seems a little unfair – you could reasonably expect to be dead before you got any money.

Medicare began in 1965 with benefits starting at age 65, with corresponding life expectancies of 67 for men and 74 for women – about 2–9 years of coverage based on gender. By 2020, the respective life expectancies were 75 years and 81 years.

But life expectancy and quality of life are very different questions, and I was still not satisfied with how to reasonably group Seniors in a way that captured relative health and vibrancy. In short – how to define the Go-Go, Slow-Go and No-Go years, and when did they begin and end?

Defining 3 Phases of Retirement

Enter Professor John B. Sloven of Stanford University and his great paper, New Age Thinking: Alternative Ways of Measuring Age, Their Relationship to Labor Force Participation, Government Policies and GDP. Sloven looked at defining age based on either remaining life expectancy (RLE) or 1-year mortality (MR) risk – the actuarially determined risk of dying in the next year. Of the two measures, I chose MR as most appropriate for my analysis – largely because it seemed to give a better feel of vibrancy of the individual in the year in question.

Specifically, Sloven used breakdowns of 1%, 2%, and 4% MR to stratify people demographically as they moved into old age. This is an objective way of measuring the relative age of older Americans and seems much more realistic than using arbitrary chronological age of 65 used in the ’30s or ’60s for Social Security or Medicare respectively. Since Professor Sloven did not assign any categories to these MR classes, I have used:

- MR = 1% to 2%: Go-Go Years

- MR = 2% to 4%: Slow-Go Years

- MR = 4%+: No-Go Years

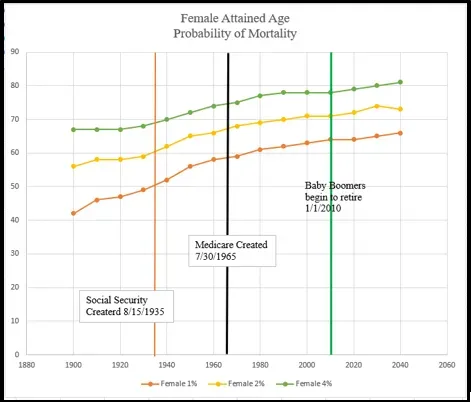

With these categories in mind, let’s look at the MR graph (Figure 1) for females, showing the age for attaining each of these categories.

All the data used in this analysis can be found in the Life Tables for the United States Social Security Area 1900–2100. The bottom line (Female 1%) in Figure 1 shows the actuarial determination of the age when American women reached 1% expected MR, growing from around age 50 in 1935 (the year Social Security started) to approximately 65 today. The 1% MR line marks the lower limit of the Go-Go years and is projected to reach 67 in 2040. As shown by the Female 2% line in the chart, in 2020, American women reach the entry into the Slow-Go period around age 71, and the No-Go category (Female 4%) just short of 80.

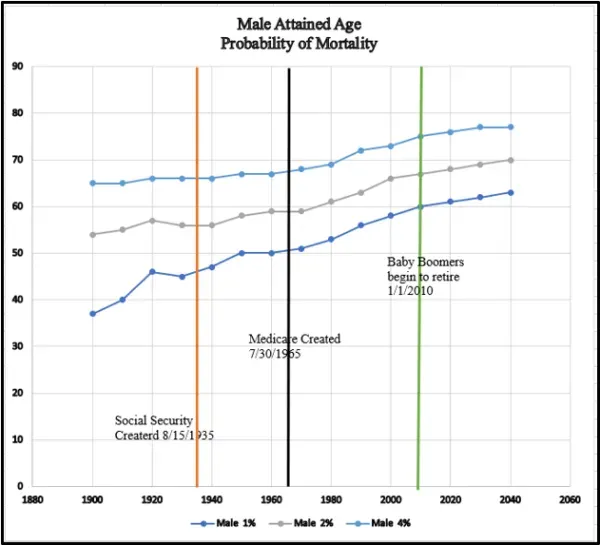

Corresponding data for males is shown in Figure 2. All the ages for entry into the age categories (Go-Go, Slow-Go, and No-Go) for men are younger than corresponding ages for women. Women generally live longer than men and have a longer life expectancy until age 100.

As an example, in 2020, men entered the Go-Go years at age 61, versus age 64 for women. Men, however, have enjoyed the same or greater absolute and percentage age gain in all the MR categories than women. For example, the age of 1% MR for men has advanced from about 46 in 1935 to 61 in 2020 (15 years or 32.6%). The corresponding ages for women are 50 and 65 respectively (15 years or 30%).

Why 65 Is The New 60

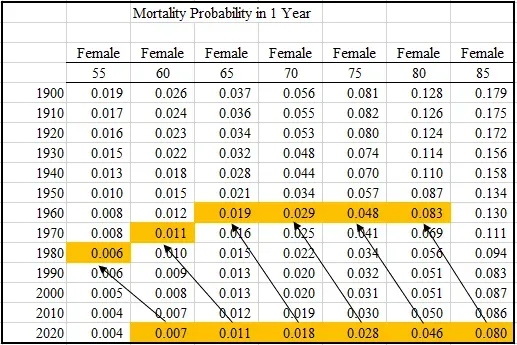

Another way to think about this phenomenon is through the often-used phrase, “65 is the new 60,” or similar age comparisons. The concept is that people remain young longer and can enjoy the relative benefits of youth into later chronological years of life. I have shown this analysis graphically below, displaying the 5-year relative age shift for women. As an example, in 2020, women at the age of 60 had a 0.007 MR, which approximately corresponds to 0.006 in 1980 – in 4 decades, 60-year-old American women were at the same point in MR risk as 55-year-old women in 1980. I have shown the 5-year shifts below and note that the 5-year shifts required between 4–6 decades (1980–1960) for all age groups for women.

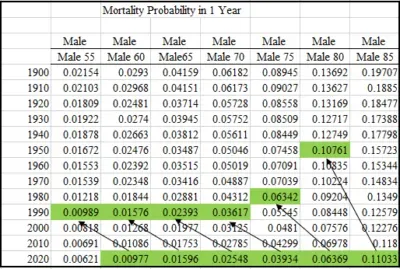

The analysis for men is similar. For example, a 60-year-old man in 2020 has an MR of 0.0097, which corresponds to the value of 0.00989 for a 55-year-old man in 1990. This correspondence is shown with green cell values and arrows in the chart above.It is interesting to note that all of the 5-year shifts for men through the age of 75 correspond to values in 1990. Looked at another way, men between 60 and 75 were the same relative age as men 5 years younger in 1990. For men aged over 80, however, these relative gains require 5 decades to accomplish, and men over 85 must go back to 1950 for a direct comparison. Another way to look at it is that men over the age of 85 are relatively old, and always have been.

In Closing

Like all population-based analyses, this framework is an important concept for individuals, but should not be considered predictive at the individual level. Go-Go, Slow-Go, and No-Go are relevant (and humorous) sub-groups, but how an individual may pass through them depends on the person. We all know people who have been struck by early illness or death, and people who defy the aging bands until very old age. But both groups of people are anomalies and do not diminish the value of the framework as a working tool for Medicare planning purposes